Edelman: Hack reveals why he changed his name and the journey it put him on

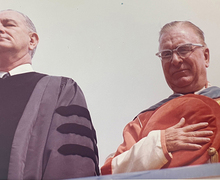

Courtesy of KJ Edelman

KJ Edelman changed his name the moment he stepped into The D.O. Here's why.

Get the latest Syracuse news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe to our sports newsletter here.

The first time you walk into The Daily Orange, you’re going to get berated with questions. What grade are you? Who do you know here? What stories did you write? Those are the easy ones.

It was 2017 and I had just written an atrocious first profile on cross country runner Kevin James (short is K.J.). I went through the cycle of questions, trying to seem equal parts smart and chillax. As I attempted an Irish exit down the steps of 744 Ostrom Ave., the sports editor at the time simply asked me, “By the way, what do you want your byline to be?”

It was expected, but I honestly had no clue what to respond. My family, my freshman floor and everybody I had ever met knew me as “Kyle Edelman.” But something in that moment compelled me to say “KJ.”

I didn’t know what it was. The name was a self-proclaimed high school nickname that never stuck. Maybe I wanted to continue the joke. Maybe I needed a reset. Couldn’t dying my hair or wearing sweater vests suffice? I was going to have to make up a very believable explanation for why I did it. I’d have to change my MySlice account, then my resume, then my email, then my social media. All for a joke?

Then, I watched a home video earlier this year. Twenty-two minutes into a 2001 clip of me splashing water in a kiddy pool, my father, Steven, started calling my name, “Kyle, Kyle, Kyle … KJ!”

I couldn’t fully remember why I changed my name because I can’t remember the man who gave me that name. My first memory was his lifeless body laying face down in our living room. It was a heart attack, his type known as the widow-maker, and I was just a kid. My mom went back to work two weeks after he died. Some photos of him appeared around my house, but I didn’t ask to see more. I never really asked about what he was like.

I don’t know Steven. Well, I know chunks. He loved Rusty Wallace and the New York Yankees. He cooked a world-class vodka sauce pasta. And he wanted his firstborn son to be a KJ someday, not a Kyle.

We, as journalists, spend so much time getting to know everything about our sources. But I often wonder: Do we try to learn about the people closest to us that same way? Because I sure don’t.

I made it my mission to learn about my father. The same routine procedures that I learned in high school would be applied to a man that I unknowingly tried to ignore. I thought a bit of reporting could remedy years of trauma.

The pain wasn’t always obvious. When I was younger, my little brother Dylan and I individually made up an imaginary second parent. When we’d get mad or frustrated, we’d say we were going to our dad’s house. He was, instead, five miles away buried in a Jewish cemetery. Visits were usually for special occasions and Father’s Day. A couple of times I drove by during a particular rough period in high school looking for some closure.

Still, I’d be able to move on from those moments after a couple of days. When I realized the reason behind my name change, I couldn’t shake the feeling. I started to ask more about Steven with this column in mind. I’d put it in to-do lists, and it’d be the last thing left every week. It was one goddamn text.

As I built up the courage to finally reach out last week, my stomach would sink in between every message. Not sink in the way a source recants or you screwed something up, but a true case of FOMO. Why had I waited years, decades to ask, and what did that say about me?

The version of my father I had been told about was the eight-year period he knew my mom. That’s missing 30 years of his life. A couple days ago, I called my uncle Gary who said he was looking forward to talking about Steven. After all these years, I was a bit surprised. I’m not that close with my dad’s side of the family. Maybe it was his death, or how far we all live, or some other factors I don’t know a lot about.

There were the versions of my dad I knew. The athletic young kid, a daredevil at times, who could light up a room. The great chef who fell deeply in love with my mom the first time he met her. The man who struggled with his weight, struggled coming to terms with his Tourette syndrome and at times struggled to be honest with himself.

Then there were all the versions I didn’t know. The moments where I was forewarned, “What I’m gonna tell you isn’t going to please you.” That he bounced from job-to-job without much direction following my grandparents’ divorce. That he worked for a trucking company despite not having a license the entire time my mom knew him. That he was once homeless in Chicago and went to a group home in East Meadow, New York, to bounce back after bouts with depression and anxiety.

The happy ending should’ve been that Steven rescued himself. That someone in his situation could have turned to drugs and spiraled out of control, but didn’t. “That’s the amazing redemption story of your dad,” my uncle concluded.

But Steven’s redemption story didn’t end like it should. He kept his high cholesterol and heart issues private near the end. Gary, a doctor, once told his brother, “If you don’t get your health together, you won’t live to see your kid graduate college.” Steven put in the work. He lost more weight than he ever thought he could and then some. The day before he died, the four of us took family portraits at our local mall, and many still remark he looked the healthiest he had ever been.

It should’ve been enough. I’m a week away from graduating. It’s been almost 20 years since his death.

Conversations with my uncle were the kind I needed to hear: the humanizing ones. Yes, I marked some people off the list, but I hope this isn’t the end. Talking to them led to some of the most honest conversations I’ve had with my mom in years.

When I asked my mom for the coveted photos of my father I thought she was hiding from me, she sent me 41 of them. I’d never seen most of them before in my life. I left the text message unopened until late in the night. My roommates had left for the bars, and I was alone in my dimly-lit living room. I swiped through them one by one, examining Steven’s facial features, his bald spots, birthmarks, even what kind of outfits he’d wear. They looked so much like me, too much like me. I couldn’t hold it in. I needed to cry.

Two summers ago, I got a tattoo of his name on my left bicep, and when it gets warm out a lot of people ask about it. My “dead dad,” I often say, to the horror of whoever asks. I joke a lot about Steven because I like to think he’s laughing along.

When I think back to the anniversaries, his funeral, even my first memory of watching him die, I never get emotional. In those memories, he’s just a person I never knew. But seeing him in those photos present, smiling, so excited to be holding my small body felt like the first time I’d really seen my father.

I’ve concluded my reluctance to get to know him wasn’t shame, but because I may have known more about him than I thought. And imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. I changed my name to the two letters he dreamed I was called by. He loved sports, so I became a sports reporter. He had two tattoos, and I got two in similar spots. When I saw a picture of him rocking a mullet, I regrettably tried the same (and don’t even get me started on his mustache phase I’ve tried to emulate).

I may have spent too much of my life wallowing on how disconnected the two of us are when I could’ve focused on the similarities. So I’m going to live the life he wanted me to have, even if it means I’m plagiarizing a bit.

— 30 —

KJ Edelman was the Digital Managing Editor for The Daily Orange, where his column will no longer appear. He can be reached at kjedelma@syr.edu and on Twitter @KJEdelman.

Published on May 13, 2021 at 1:18 am